A robotic skin enables machines to have a sense of touch and perceive pain

British researchers have developed a robotic skin capable of sensing pressure, temperature, cuts, and even pain, which could forever change the way robots interact with the physical world… and with us.

Robots that feel pain? Welcome to the future that science fiction dared not write. Until now, imagining a robot that feels like you or like me was the stuff of dystopian tales or existentialist androids in cult movies. But reality has just overtaken Isaac Asimov and company.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge and University College London (UCL) have developed a robotic skin that not only senses but also has the ability to process pain.

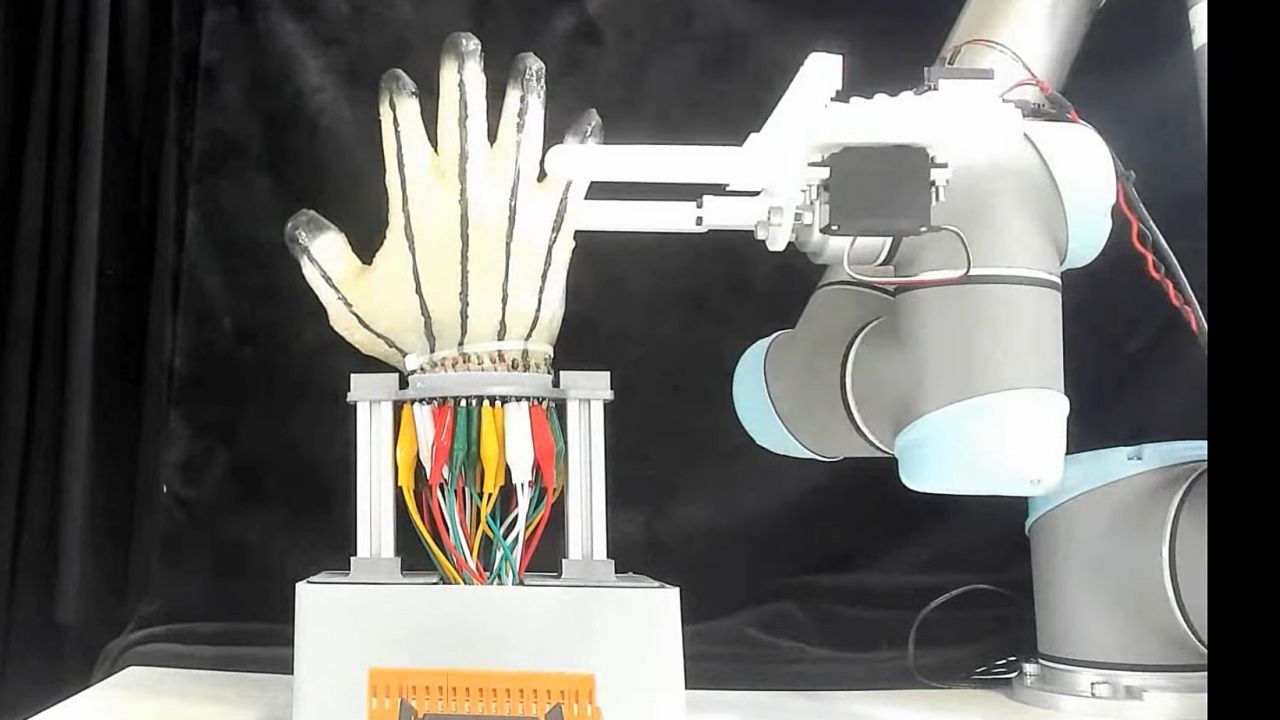

What's the secret? A flexible and conductive gel that turns the entire surface of a robotic hand into a single, large, and sensitive sensor. No scattered sensors or modular technology. Here, every centimeter of skin feels, and it does so with astonishing sensitivity: more than 860,000 tiny pathways to detect pressure, heat, cold, or cuts… all at the same time.

With just 32 electrodes, it collects more than 1.7 million data points

From glove to artificial nervous system

The fascinating thing is that this skin does not require complex integration: it is put on like a glove over a robotic hand and turns the android into something dangerously similar to a human. Technically, we are talking about multimodal detection, that is, the ability of a single material to register different types of tactile stimuli.

Until now, this was achieved with specialized sensors that were frankly expensive, fragile, and inefficient. But this new material —a soft and electrically conductive hydrogel— changes everything. And it does so with just 32 electrodes placed on the wrist, enough to collect more than 1.7 million data points in laboratory tests.

From a gentle touch to a scalpel stab, this skin feels it all. And with the help of machine learning, it can interpret those signals with remarkable precision.

Presentation video from the University of Cambridge

What if robots also “suffer”?

One of the most intriguing —and somewhat disturbing— aspects is that this skin does not just detect, but can distinguish pain. We are not yet talking about conscious suffering, but rather a mechanical ability to differentiate between gentle contact and potential harm.

This raises philosophical questions that we still do not know how to answer: if a machine feels damage and avoids it, are we facing a primitive form of conservation instinct? What ethical implications does a robot that detects that you are making it suffer have?

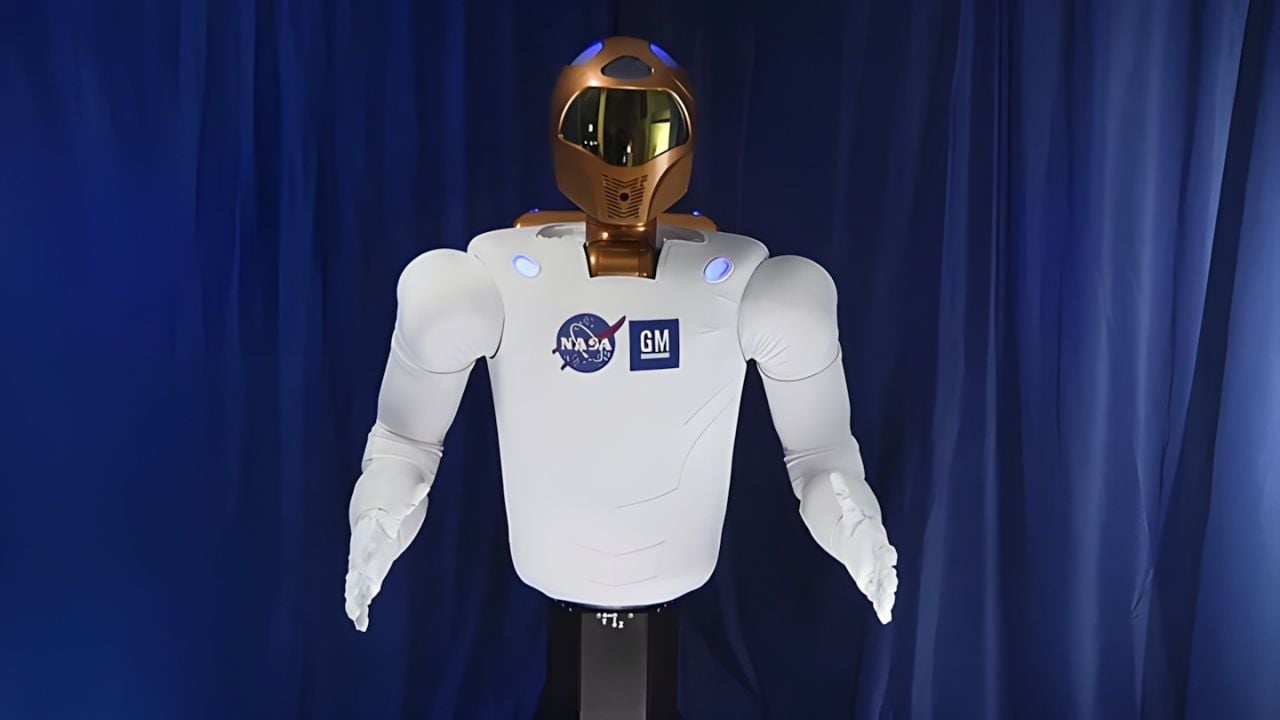

On the other hand, the potential uses are as varied as they are astonishing. From assistance robots with a more natural and safe touch, to human prosthetics capable of restoring the sense of touch, to applications in extreme environments such as disaster rescue or space exploration.

Imagine a firefighting robot that can feel if a surface is too hot, or an automated worker that detects a gas leak by the temperature change before anyone notices.

What’s next: more realism, more humanity

The next step, according to the researchers themselves, is to improve the durability of the material and test it in real-world tasks. And although it still does not match the sensitivity of human skin, they assure that it far exceeds any other available robotic tactile system today.

Science fiction has been a constant source of inspiration for engineers, but if one thing is clear, it is that it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between what we imagine and what is already real. Today, a robot can feel heat, cold, and damage. Tomorrow, it may ask you not to tickle it.

* This news is an AI translation of the original content. Motenic.com is part of Motor.es.

Fuente: University of Cambridge | University College London | Science Robotics.